Decomposition, c'est quoi?

The basic perspective I want to adopt in this class is one of discovery. Both linguists analyzing and children learning a language are engaged in the process of discovering structure.

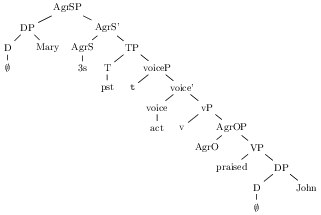

With this in mind, consider the kind of syntactic analysis a layperson might give to the sentence “Mary praised John,” and contrast it with one that a linguist might give.1 The lay analysis might (if constituent based) assign praised John to a constituent (‘VP’), and then Mary and this VP to a constituent ‘S’.2 The linguist might have a rich hierarchy of functional projections, for example: V-AgrO-v-voice-T-AgrS, as well as multiple movements (for case).3 A sympathetic read of this is that the linguist’s analysis is a more fine-grained version of the lay analysis.

| lay | linguist |

|---|---|

|

|

One reason for thinking that there is some relation between them, is that the trees themselves (ignoring the leaves) are structurally similar in a way that can be made formally precise: we can associate each node of the linguist’s tree with a corresponding node of the naive tree in such a way that dominance relationships are respected. More precisely, let every non-leaf node in the extended projection of V in the linguist’s tree map to the VP in the naive tree, and every (non-leaf) node in the extended projection of T in the linguist’s tree map to the S in the naive tree.4 Thus in a formally natural sense, the linguist’s analysis is a more precise version of the naïve analysis.

But how could we (or a child) arrive at such a refined analysis, starting, say, from a naïve analysis? Is is just some cosmic coincidence that the linguist’s analysis and the naïve analysis have converged? Or is there some systematic way to arrive at the linguist’s analysis from the naïve one?

A straightforward observation is that our refined ‘domain’ analysis (the TP-domain, the VP-domain etc) results from the naïve one by ‘splitting’ one projection into two. Ignoring the actual words for a moment, we can break apart the naïve VP (= [VP V NP]) into a VP-shell (= [vP v [VP V NP]]). Repeating this over and over eventually yields to us all of the refined projections we might like.

This idea seems promising, but we have a number of questions we have to answer:

- how exactly does it work?

- what should we do with the (whole) words we started with?

- how does agreement come into play?

- how do we decide whether something should be moved or not?

To answer these questions, we will need to be more precise than we normally need to be when conducting linguistic analyses.5

The next post will present an elementary formal introduction to minimalist syntax. We will spend some time getting familiar with this formal system, and then we will return to the above questions, and investigate them in this context.

Readings

If you would like to read some of the primary literature on this formalism, here are some suggestions.

- Stabler (2011) Computational Perspectives on Minimalism; pages 1-7

- Stabler (2010) After GB; pages 1-7

- Stabler (1997) Derivational Minimalism

-

I am having some difficulty including pretty graphics at the moment. Please bear with me. ↩︎

-

[\(_{S}\) [\(_{{NP}}\) Mary] [\(_{VP}\) praised [\(_{{NP}}\) John]]] ↩︎

-

[\(_{AgrSP}\) [\(_{{DP}}\) Mary] [\(_{TP}\) T [\(_{vP}\)

t[\(_{v'}\) v [\(_{voiceP}\) voice [\(_{AgrOP}\) AgrO [\(_{VP}\) praised [\(_{{DP}}\) John]]]]]]]] ↩︎ -

This mapping relationship between the linguist’s and the lay person’s tree is called a (structure preserving) homomorphism, and it is an accepted formal notion of similarity of structure in the mathematical community. Note that it is not quite right yet, as we have to ignore the pesky leaves which do not participate in the correct dominance relations. This can be corrected by moving to a different (but equivalent) representation of syntactic structure, which we shall do later. ↩︎

-

This makes sense, of course. You don’t need to be as precise about your theory when you’re using it to analyze things, as you do when the object of analysis is your theory itself. ↩︎